Since its release in 2011, From Software’s Dark Souls has had an extraordinary influence on video game culture, helping to re-define and invigorate the action-RPG genre. Widely regarded as one of the best video games ever made, Dark Souls spawned two highly successful sequels; while its spiritual successor, Bloodborne, is one of the top-rated games on the PS4. Dark Souls also profoundly shaped the wider world of game design: they say imitation is the highest form of flattery, and the design philosophy of Dark Souls was a clear influence on two of the best games of recent years, Zelda: Breath of the Wild and The Witcher 3. There’s also an entire sub-genre of “Souls-like” games now, such as hardcore Japanese supernatural slasher Nioh, all of which owe an explicit and obvious debt to From Software’s classic.

From Software was a relatively minor Japanese studio before making Dark Souls, chiefly known outside Japan for PS3 exclusive Demon Souls, a critically successful hardcore action-RPG. Like that game, the development of Dark Souls was overseen by Hidetaka Miyazaki. Thanks to his work on the Souls series and Bloodborne, Miyazaki has earned a reputation as a visionary game director, and with good reason. He had a bold and ambitious vision for Dark Souls, which eschewed many well-established video game tropes and mechanics, harking back in significant ways to the early days of video game design. In particular, Miyazaki aimed to evoke the sense of a gameworld that is much larger and richer than the player can directly know or understand. The trend in recent years has been for RPGs to load their games with enormous amounts of exposition and lore through long cut-scenes, endless dialogue, in-game books and journals, and so on, theoretically satisfying the player’s desire to learn about the fictional world. But Miyazaki follows a different approach: while Dark Souls does have a complex, fascinating back story, this is communicated to the player slowly and partially through direct observation, brief item descriptions, and occasional exchanges with in-game characters. Dark Souls thereby embodies that motto of good storytelling, “show, don’t tell”; and it also demonstrates a philosophical understanding of narrative that reminded me of the approach of authors like Hemingway and H.P. Lovecraft.

While restricting the volume of narrative exposition, Dark Souls also dispensed with many of the props and crutches that gamers have come to rely on over the past decades. There are no maps in this game: the onus is on you to remember how the game’s sprawling, labyrinthine world is connected. Of course, you’re welcome to draw your own map as you progress. More unconventionally, unlike most real-time games made in the last 30 years, Dark Souls has no “pause” button. This is common for online-only games like World of Warcraft, but extremely rare for single-player focused games like this. The inability to pause does ratchet up the tension: if you’re losing a fight, or you want a breather or time out, you can’t just pause the game – you have to press on until you find a point of relative safety. This adds meaningfully to the game’s immersive atmosphere.

One of Dark Souls characteristic features is its “bonfire” mechanic. Reaching new bonfires is essential, as dying causes you to respawn at the last bonfire you rested at. Bonfires are situated at regular intervals throughout the gameworld, and are havens of calm where the player-character can rest, replenishing health and filling the “Estus Flask” (the main way to restore your health while exploring). Moreover, you can only spend “Souls” at bonfires: acquired by defeating enemies, you use these to level up your attributes. Resting at bonfires is therefore essential… but, just like dying, resting at a bonfire causes most enemies to respawn. There are a few exceptions to this – mercifully, bosses don’t respawn – but considering that almost everything you encounter in Dark Souls is capable of killing you, the decision to rest at a bonfire is often a fraught one, contributing to the finely-balanced sense of risk and reward that distinguishes Dark Souls. It’s exacerbated by the fact that if you die, your character “drops” the souls you’ve earned. You can retrieve them by returning to the place you died and touching your bloodstain, but if you die again en route, the souls you’d earned before are gone for good.

Neither does Dark Souls feature difficulty levels: what you see is what you get. Most games, especially in the West, feature adjustable difficulty levels which allow you to make the game easier. That doesn’t apply here, and Dark Souls forces you to learn and improve if you want to make progress. Because the game saves your progress every few seconds, it also negates “save scumming”, which is the practice whereby you keep back-up save files of a game state you can return to if you make a decision you regret. In Dark Souls, you have to live with everything you do, including all your mistakes. If you consume an item in an effort to defeat a boss, but you fail and die, then the item will be gone from your inventory when you respawn. You have to fully commit and take responsibility for every decision. Most RPGs rely on their stories to draw you in, but Dark Souls is unique in how the gameplay mechanics deepen your engagement and investment in the overall experience.

None of this would work but for the fact that Dark Souls is such a well-balanced and well-designed game. The game is notoriously difficult, but it rarely (if ever) feels gratuitously unfair: there’s always a way forward, it’s just that you either haven’t worked out the strategy to defeat your enemy, or you lack the competence to execute the strategy. In the first case, you need to observe and prepare better; and in the second, you need to practice your skills at dodging, blocking, parrying, and so on. Indeed, the console version of Dark Souls which shipped with all the DLC was sub-titled Prepare to Die, and in this game, dying and respawning is a central part of the process. You need to use your failures as a learning experience and persevere in order to ultimately triumph.

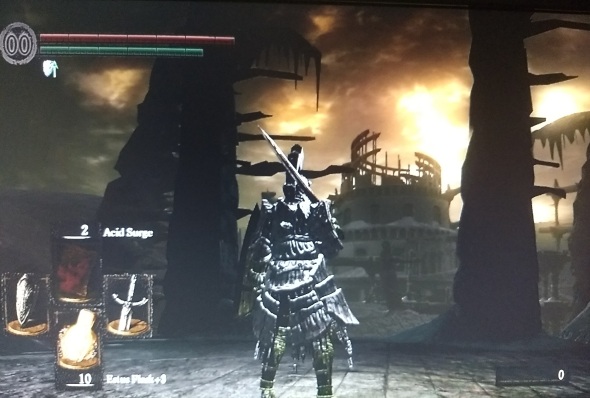

Dark Souls does have a class system, in that you choose a class when creating your character, but there is a lot of flexibility in where you go from there. In general, especially for a first playthrough, you’re best advised to stick to familiar archetypes: build your Endurance to use heavy armour and weapons if you want to play a tanky Knight; build your Dexterity if you want to play a skillful rogue; or build you Intelligence and/or Faith to play a Sorcerer or Cleric. But it’s possible to play around with hybrid builds, and the game is balanced so that most approaches are viable. However you choose to play, sooner or later you’re going to have to get to grips with the game’s basic mechanics. This is a skill-based game, not a war of attrition, and you have to learn the game’s rules and improve your competence if you want to prevail.

Dark Souls is a third-person action role-playing game, and for the most part the experience is deliberately paced and tautly controlled; even though your path through the game is largely up to you. You’ll encounter all sorts of undead and monstrous enemies, coming in all shapes and sizes, and you have to stay alert and keep your wits about you. Unlike most RPGs, this isn’t a game where you can go on autopilot and mash the attack button once you’ve gained a few levels: most enemies have the ability to kill you within a few hits, and carelessness will result in a swift trip to the last bonfire. You need to learn and remember enemy attack patterns, know when to dodge or block, and wait for an opportunity to strike. This is amplified with the game’s monstrous bosses: Dark Souls contains some of the most devilishly inventive, exciting, and brutally difficult boss fights I’ve ever experienced. I’ve spent whole Saturday afternoons working on a single boss fight, against the likes of the Capra Demon or Great Wolf Sif, dying countless times, but constantly refining my strategy and getting a bit closer each time. Sometimes, patience is the key to success, and you need to wait, and wait, and wait, for an opportunity to get a hit in against an enemy who is much stronger, faster, and larger than you.

The upshot of all this is that, while some boss fights can be frustrating as well as physically and emotionally exhausting, you’re rewarded with a sense of genuine achievement when you finally triumph. In recent years, many game developers have gone down a sinister route by manipulating the human brain’s hard-wired relationship to reward and achievement through devices like loot boxes and so on. In contrast to this approach, Dark Souls cultivates and encourages a positive sense of achievement that, in fact, mirrors the psychological process of gaining confidence by coping with suffering, improving your competence, and overcoming adversity; which is the very process you’re literally and metaphorically acting out in-game.

One of the fascinating things about the world of Dark Souls is its elaboration and exposition of familiar mythological tropes and archetypes, and it’s a rich source for narrative analysis and deconstruction. The whole story is an example of Jung’s “heroic journey”; and if the point of the Hero’s Journey is indeed to test and demonstrate the process of maturation and the stability of the ego, then playing Dark Souls itself acts as a sort of test of the player’s ability to continue in the face of adversity. I should point out that it took me years to finish this game. I first tried to play Dark Souls in 2013, only making it past the first couple of bosses before the game overwhelmed me. I thought its world was fascinating, but I couldn’t get to grips with the gameplay mechanics or punishing difficulty. But I always promised myself that I would return to it, one day, and try to complete it. I’m pleased that I finally did so, because playing Dark Souls proved to be one of the most exhilarating and rewarding experiences I’ve had in gaming. It also gives me the confidence to tackle other “Souls-likes”, such as Bloodborne.

That said, I had to make a couple of concessions in order to get through the game. Dark Souls has an original mechanic whereby other players are able to “invade” your game and kill you, further complicating an already stressful experience. There are ways to avoid this, but I preferred to just remove the possibility altogether by playing offline. You also receive relatively few cues on what to do and where to go while playing. Ideally, I suppose you should just wander around and experience everything “properly” without external help, but I knew that if I tried to do that, I’d never complete the game. So, when I returned to the world of Dark Souls this year I used a walkthrough to help me explore, and knowing where to go next meant the game vexed me a lot less than it otherwise would have. There are also some areas which have obscure stipulations to access, which I’d have never found naturally without using a guide.

Dark Souls was an impressive-looking game when it first released, and it stands up pretty well today. While the graphics aren’t technically perfect, it features an extraordinary art style and some of the best monster design I’ve ever seen. Although it’s a Japanese game, Miyazaki draws inspiration from European history, architecture, and mythology, and the resulting cultural fusion feels simultaneously familiar and strange. There are occasional technical problems, including some notorious frame rate issues, and an occasionally temperamental camera which can cause you to walk off ledges or which can get stuck behind a gargantuan boss. The game’s sound design is minimalist, the subdued musical score in keeping with the sombre subject matter; but there are some memorable interludes. The multi-platform release of the Dark Souls remaster is imminent, but from the trailers these ports don’t look to be significantly better than the original version. If you still have the original, but never played it, my advice would be to stick with that rather than shelling out again for the port.

Including the DLC, my playthrough of Dark Souls took me around 65 hours. It was an engrossing, enthralling experience, and I was sorry when the time came to finish the game. For a game with so little dialogue, it establishes an extraordinary pull on your emotions. If it weren’t for the fact that I’m so keen to play this game’s sequels, and related titles like Bloodborne, I would have been sorely tempted to do a second playthrough. Which is the last thing I thought I would ever say about Dark Souls. It’s not perfect, and I don’t think I can give a perfect score to a game that took me five years to complete, but Dark Souls is undoubtedly one of the greatest and most important video games ever made.

9.5/10